Who were the Mayans, and why did their thriving civilization suddenly collapse and fail? It is a question that has puzzled historians and explorers for decades—one which has given rise to a variety of theories, none of them entirely adequate. We may never know how and why a people that had endured for thousands of years abruptly vacated cities, colossal temples, farms, and homes, largely disappearing into the annals of history.

Table of Content

When did the Mayans civilization

It is believed that early Mayans arrived in what is present-day Guatemala as early as 11,000 B.C. and that they arrived there from Siberia via a land bridge. Over time, these hunter/gatherer tribes grew and expanded into Mexico and parts of Central America. It was not until around 2,000 B.C, however, that the Maya civilization began to take root and thrive. Following the age of hunter/gatherers, the history of the Maya is defined by five major periods.

The Pre-classic or Formative Period, which was marked by the advent of villages and organized agriculture, began around 1800 B.C. The Pre-classic Maya were more advanced, displaying cultural traits like city construction and pyramid-building. Then came the Middle Pre-Classic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C. During this period, farmers expanded their presence in the highland and lowland regions and came under the influence of the expanding Olmec Empire. Many aspects of Mayans culture were derived from the Olmecs, including religious and cultural traits, as well as the Maya calendar and numbers system.

The Golden Age of the Maya Empire

The Classic Period was also known as “The Golden Age.” The Golden Age began around 250 A.D. and lasted until the Terminal-classic, or Period of Disaster, in the late eighth century through the end of the ninth century A.D. The period from that time until the fifteenth century is known as the Post-Classic Period.

The earliest Maya spoke a single language, but by the Pre-Classic Period, a diversity of languages had developed. Today, there are some 70 Maya languages spoken in modern-day Mexico and Central America. Most of the 5 million or so Mayas also speak Spanish.

Download this Article in PDF Format

Get a well-documented version of this article for offline reading or archiving.

Download Now (2.1 MB)The main seats of Maya civilization were environmentally and culturally diverse. They consisted of Belize and western Honduras, the northern Maya lowlands on the Yucatan Peninsula, the southern lowlands in northern Guatemala and adjacent portions of Mexico, and the southern Maya highlands in the mountainous region of southern Guatemala. As you might imagine, climate conditions, terrain, water, and other natural resources, were just as diverse.

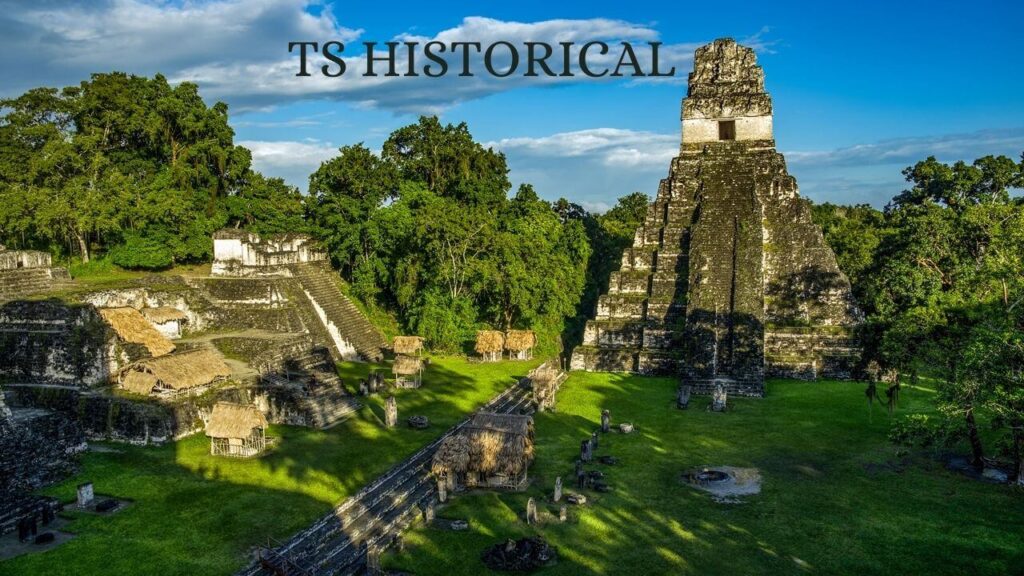

The longevity of the Maya civilization is attributed, in part, to their adaptive abilities and their skill at making the most of what resources were available. The Golden Age saw Maya civilization grow to some 40 cities, including Uaxactún, Copán, Tikal, Bonampak, Calakmul, Palenque, Dos Pilas and Río Bec. These cities were heavily populated, the largest of them containing upwards of 50,000 people.

Rainwater, Technology, and Survival of the Maya

At its peak, the Mayans population is thought to have grown to as many as ten million. The building of massive temples, palaces, housing, and other structures had already commenced. Underground rivers and sinkholes called cenotes provided much of the water for personal use and irrigation. In regions that had no natural water sources, the Maya used ingenuity to supply their large populations. The region called “Puuc” (Yucatan Peninsula) was one with no streams, rivers, lakes, or springs.

The Maya there used massive systems of cisterns called chultuns to collect and store rainwater. In the fabled city of Palenque, Mayas devised vast aqueduct systems that ran beneath the city’s walls and streets. The Mayans economy was largely based on agriculture and trade. The crop of premier importance was corn, but the Maya also grew red and black beans, squash, chilies, tobacco, and other crops. Over centuries, they developed and refined irrigation systems and expanded into terraced gardening.

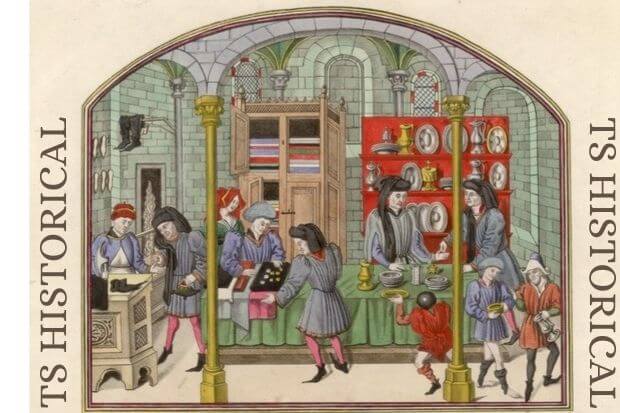

They also raised a variety of animals, including cows, pigs, and goats. Markets were established, and laws were enacted to ensure that agriculture and trade ran smoothly. As trade routes were established between various city-states, the populace grew and flourished. Evidence found in the past few decades indicates that trade was widespread. Artifacts show that many goods were moved considerable distances, despite the difficulties and the lack of beasts of burden. Chemical tests have confirmed that some of these items were transported at great distances. Other goods of trade included such diverse products as cotton mantels, slaves, flint, obsidian, seashells, quetzal feathers, tools, and salt.

There were various forms of payment, all of it based on trade rather than monetary units. Smaller purchases were mostly paid for with fish, maize, salt, or any of the other commodities, while larger purchases might be paid with gold, silver, or other “luxury” goods.

The Maya civilization consisted of city-states that encompassed considerable Mesoamerican areas and thousands of square miles. There was no single ruler, rather, a collection of lords and kings who zealously guarded their own cities and holdings. Although much of the prosperity of the Mayans was gained through trade, there was also warfare between competing city-states.

A military campaign might be launched for a variety of reasons; there were conflicts over control of trade routes, forced compliance with the paying of tributes, and attempts to annex territory through attacks on a bordering state. Little is known about how military organizations were formed or trained. Conflicts are depicted in Maya art from the Classic Period; wars and victories are found in hieroglyphic inscriptions but do not provide information on the causes of war or the form it took. From as early as the Pre-Classic Period.

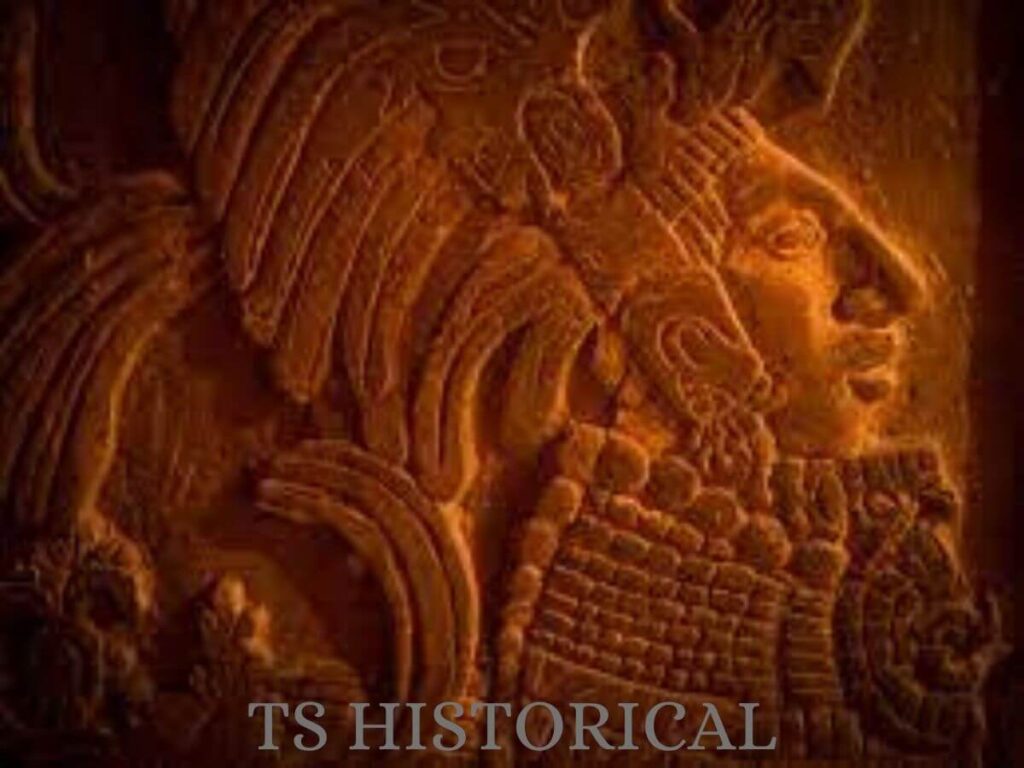

The head of a polity was expected to be a fearless warrior; some are depicted with trophy heads hanging from their belts. By the time of the Classic Period, however, trophy heads no longer appeared in such depictions; rulers are seen as looming threateningly over war captives. Other aspects of Mayans culture included elaborate religious rituals and ceremonies. The Maya believed in blood sacrifice and bloodletting. Rulers, kings, and high priests performed bloodletting rites for every stage in life, every important religious or political event, and for the beginning and end of calendar cycles of any significance.

The ancient Mayans believed that the most sacred blood (aside from that of the heart) was from the tongue and the ear. The piercing of ears symbolized an opening to enable the hearing of revelations from the gods. Likewise, piercings of the tongue would allow for speaking those revelations. The Mayans also practiced human sacrifice; often, the victims were captured in warfare or raids, but they were also selected from the fit, young Mayans. In the ceremonies, the victim was bound, and a priest or ruler cut open the chest and removed the still-beating heart.

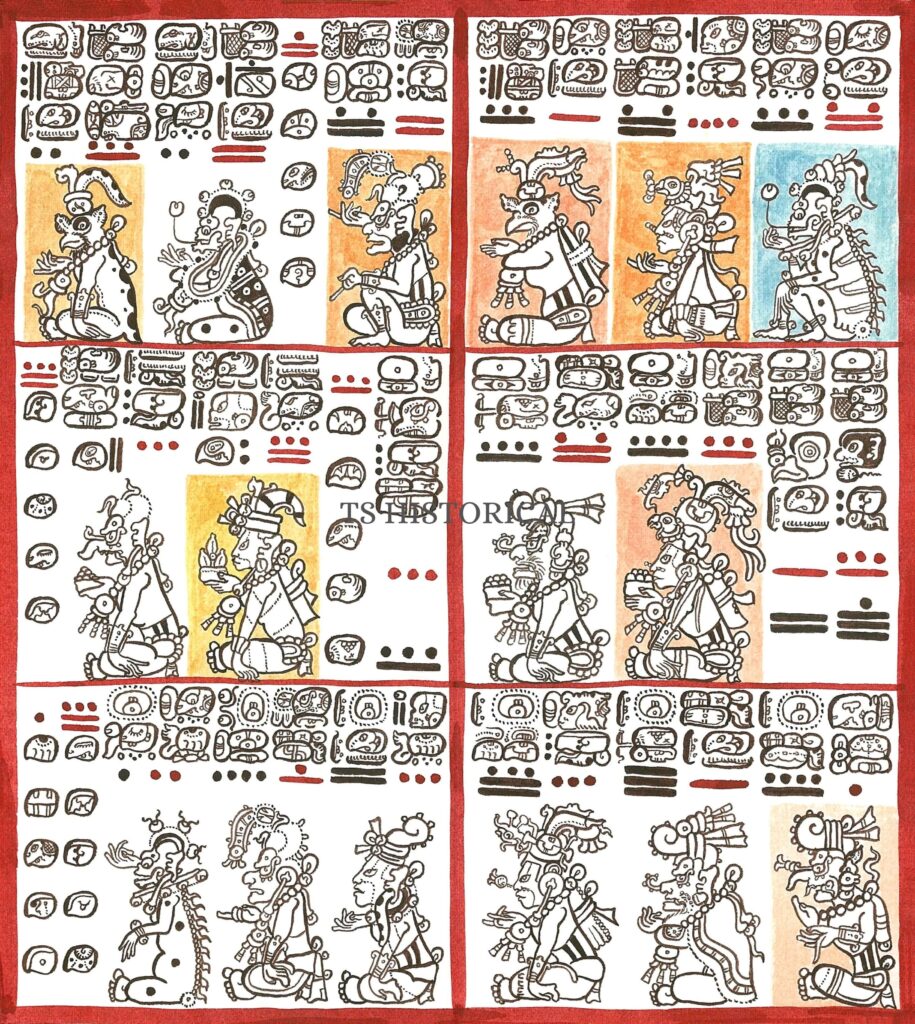

Maya Codices

This event is depicted on ancient objects and pictorial texts known as codices. These sacrifices were evidently intended to appease (or please) the various gods, and there were many, most of them tied to nature. The gods of sun, rain, moon, and corn were but a few of the deities important to the Maya.

The Maya performed other rituals to satisfy the gods and guarantee some order to the world. There were rituals for marriage, divination, and baptism. These ceremonies often coincided with calendar cycles, days considered holy, but also for special events.

A variety of drugs and alcoholic beverages was used in many rituals; inebriation was believed to be helpful in the widespread practice of divination, a ritual designed to allow direct communication with certain supernatural forces. Inebriation was thought to give one insight to interpret the causes of misfortunes like illness and adverse weather. Until the end of the Post-Classic Period, Maya kings took the lead role in wars.

Maya inscriptions reveal that a defeated king could be kept captive, tortured, and even sacrificed. For the defeated polity, outcomes could vary. Entire cities might be sacked and never resettled, as at Aguateca. In other cases, the victors might seize the defeated noble, along with his family, and imprison or sacrifice them to the gods. At the less severe end of the spectrum, the losing polity would be forced to pay a tribute to the victors. Some historians believe these internecine conflicts led to the eventual ruin of the civilization. Whatever the reason, much of the empire began to erode toward the end of the eighth century.

This is Why the Maya Abandoned Their Cities

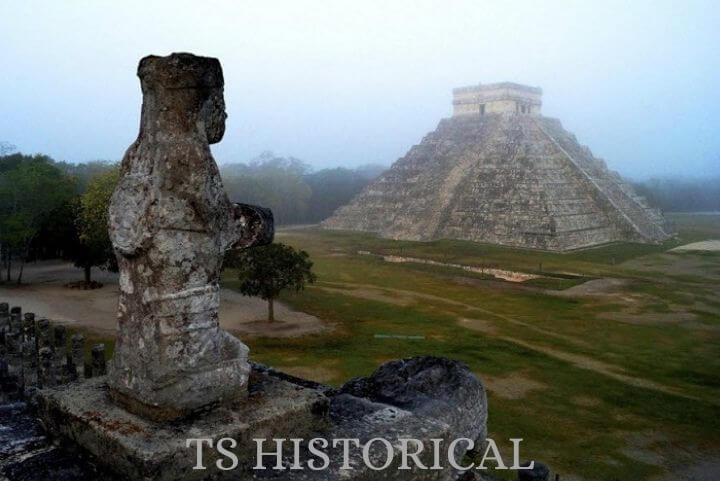

The cities in the southern lowlands were mysteriously abandoned, and by A.D. 900, the Maya civilization in that area had collapsed. However, in the highlands of the Yucatan, some cities continued to flourish in the Post-Classic Period. From A.D. 900 to 1500, the glorious centers of Chichen Itza, Mayapan, and Uxmal continued to bustle with life.

A scant century later, the Spanish invaders found most Maya living in agricultural villages. The once-great civilization lay covered in jungle and vines, left to the ravages of nature and time. Exploration of these sites began in earnest in the 1830s. By the early to mid-twentieth century, some of the hieroglyphic writing contained at those sites had been deciphered, allowing a fascinating glimpse into the history and culture of the Maya.

Excavations within the jungles unearthed colossal temples, palaces, plazas, and pyramids, all constructed from solid stone blocks fitted so precisely together that many explorers and historians have wondered if the Mayans had ‘extra-terrestrial help. Also fueling that speculation was the almost eerie accuracy of Mayans astronomy and mathematical calculations that included the famous Mayans calendar. Interestingly enough, it was Mayans astronomers who discovered that a year was not 365 days long but 364.25 days.

It was not until 1582 that Europeans stumbled across what the Mayans had known for centuries. The Mayan calendar, which was developed before the birth of Christ, is still considered the most accurate in existence. It was early Mayan astronomers who first calculated (correctly) that the journey of Venus through the expanse of the heavens took precisely 583.92 days. Calculations were kept on papyrus and carved into stone. Minute recalculations were made and recorded over thousands of years.

What happened to the Mayans civilization remains one of the world’s most enticing mysteries. There are several competing theories, but they are just that—theories. As previously noted, internal warfare between city-states may have led to the breakdown of societal norms and the eventual collapse of governing systems.

That, however, would not explain the sudden departure from populated, well-ordained cities. Some historians hold with the theory of an extreme and prolonged drought or other climate-related disasters, while others postulate a cataclysmic event (like a volcanic eruption or an asteroid colliding with earth). Yet others theorize that the Maya Empire became over-populated and simply depleted the resources needed to sustain millions of citizens.

The reality is that the demise of the Maya may have resulted from one or more of those theories or may have had an entirely different cause. We may never know. We do know that a large number of Maya survived those turbulent times. Today, their descendants comprise nearly 40% of the population of Guatemala and still live in modern-day Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico. We who visit may marvel at the stunning architecture and the artwork accomplished with rudimentary tools, plant-based dyes, and hand-mined elements.

We may experience a moment of terror as we stand at the very stone altar where human hearts were ripped from sacrificial victims, or stare in awe at the cavernous, great cenote, wondering what secrets and treasures it holds. But to the remaining Maya, this is their history, their passion. This is their heritage, their home, the land of their ancestors.

Discover more from TS HISTORICAL

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.