Table of Content

Black Death Summary

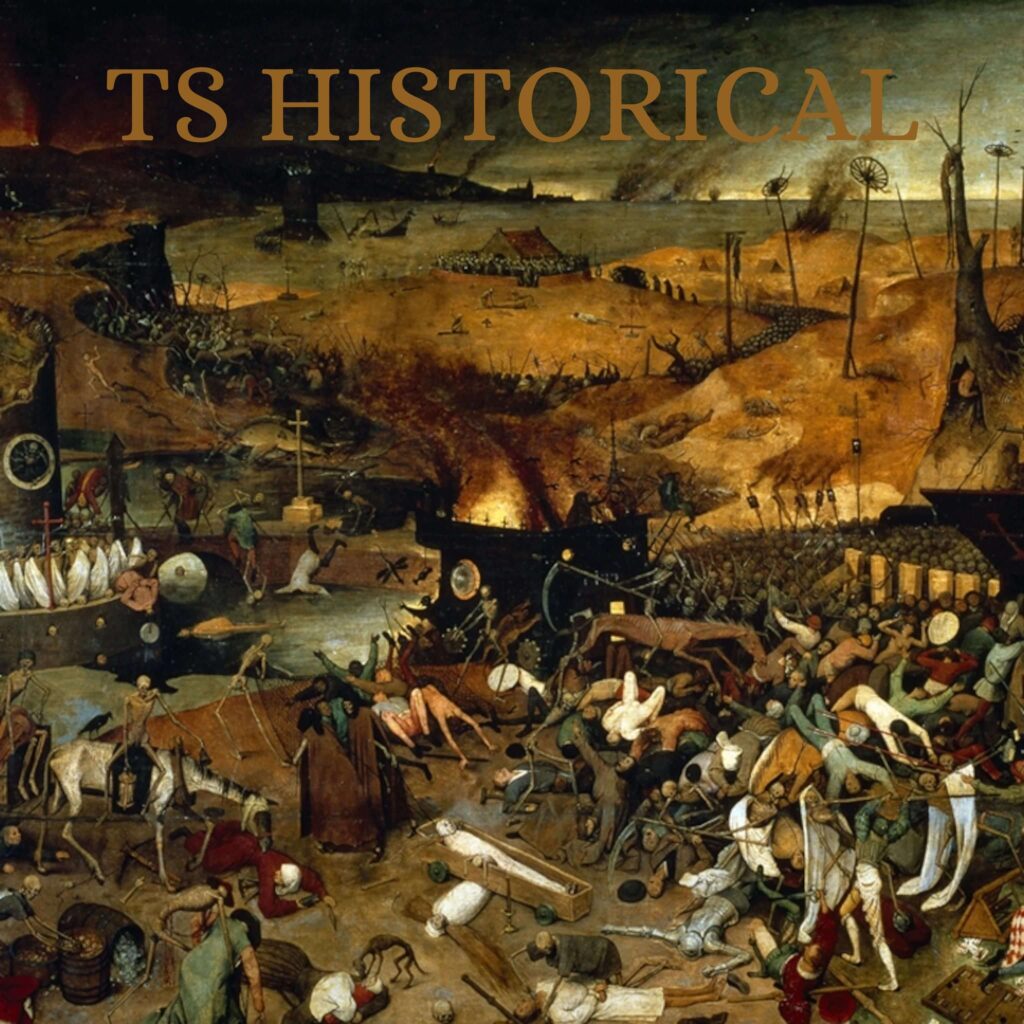

The Black Death: Nothing quite as eerie and magnificently vile has impacted the Earth as pandemics. As the initial instinct of indifference, nonchalance, and levity turned into a dreadful disquiet for most, it never dissolved for some. This phenomenon has never been restricted to a time or place; it has exhibited itself throughout the world in one form or another. Yet, in studying how the masses approached those times, we often find that many people rejected its very existence and suggested tactics for dealing with it. How could the human race have lived through the lauded and the so-called “Age of Reason” and still be plagued by a complete rejection of reason in the light of approaching pandemics?

This tradition goes back to the inception of human life; it has continued to its present form and probably will continue until the end of our species. Considering that we know the broad responses to Covid-19, can you imagine how the world reacted to similar situations in the Middle Ages? The Bubonic Plague, also known colloquially as the Black Death, is among the largest recorded pandemics in human history.

It wiped out between 25-50 million people, reaching its peak from 1346 to 1353, but the 14th-century outbreak was essentially a re-emergence. The disease had appeared much earlier, during Justinian’s rule in the Eastern Roman Empire, and had ravaged the land once already. Afterward, the Black Death repeatedly reappeared – but could never impose the same aura of death and destruction. The element of surprise was lost, and people had been studying it scientifically.

Plague of Justinian

The Black Death persists to this day, but it is not the death sentence it once was in the 6th century, the Plague of Justinian lay waste to the Mediterranean. Between 541 and 544, the plague took hold of the Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, which was the remaining contingent of the Roman Empire after the fall of Rome. Justinian could not keep his ambitious projects running, so he changed the tax code and increased taxes.

Today, the plague is sometimes remembered as the Plague of Justinian because the Byzantine emperor’s handling of the crisis worsened conditions. Researchers claim that this disease was the Bubonic Plague. Evidence points to multiple occurrences of the disease long before the 6th century. The bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, a bacteria that causes three types of plague: bubonic plague, septicemic plague, and pneumonic plague. Archaeologists have found a 5000-year-old victim of the Yersinia pestis in some human remains near the Estonian-Latvian border.

Download this Article in PDF Format

Get a well-documented version of this article for offline reading or archiving.

Download Now (2.1 MB)The most common of the three plagues is obviously the bubonic plague, in which the bacterium attacks the lymph nodes. If untreated, it continues to affect the circulatory and respiratory systems. In septicemic plague, the bacterium infects the blood and traverses through the body, making it more dangerous than the bubonic plague.

The pneumonic plague is airborne and attacks the lungs as well. It is believed that all three plagues were responsible for wiping out much of Europe in the fourteenth century. In the 1340s, the disease affected India, Persia, China, Syria, and Egypt. Many believe that the outbreak started in China and arrived in the Mediterranean through the ports. From there, it proceeded to wreak havoc on Afro-Eurasia. Different theories exist regarding the origin of the plague.

The Greatest Catastrophe Ever

The Black Death appeared in Europe with the arrival of 12 ships from the Black Sea in October 1347. As the ships docked at the Sicilian port of Messina, the people on the docks were greeted with a horrifying discovery: most of the ship’s sailors were dead, and the ones who were still alive were gravely ill and partially disfigured. Black boils full of blood and pus covered their skin.

These boils are called buboes, and they are responsible for giving the bubonic plague its name. The authorities of Sicily ordered the fleet to leave for the Mediterranean Sea, a disastrous decision that did more harm than good. The plague had started to spread – and it would not stop for the next five years, killing between a quarter and half of the continent’s population. The origins of the Black Death may be disputed, but its first definitive appearance was in Crimea, and estimates are that over 85,000 people died there from the illness.

When the Tartars from Crimea laid siege on the coastal city of Caffa, the Tartars were losing people left and right. They decided to make the most of their situation and started catapulting the corpses of their plague victims into the stronghold of Caffa. When the survivors from Caffa fled and reached Europe, landing at the port in Sicily, they had unintentionally set a series of events in action that would have severe ramifications for both Europe and Africa. From Messina, the Black Death spread to Tunis in North Africa and Marseilles in France.

Rome and Florence were part of important trading routes, so it was only a matter of time before the plague reached there. By 1348, the plague had entered mainland Italy, Spain, and France. Cities like Paris, Lyon, Bordeaux, and even London had fallen prey to the grim reality. When the plague started to take over most of Europe, initial observations of the phenomenon dismissed it as a scourge for the cursed and the evil. Interestingly, almost all groups of human beings think of themselves as saviors and detractors as malicious. For the Catholics, the Pagans were evil; for the Pagans, the religious folks were lost to an ideological constraint.

The Middle Ages were home to superstition and a public aversion to rational thinking. While it is true – contrary to widely held beliefs – that medieval times produced some marvelous technological and innovative leaps, one cannot overlook that most of the period’s knowledge was unavailable to the general population.

Most people believed that the plague was a punishment from God. People in Europe had years of warning leading up to the plague, but they were dismissive of the problems of the Eastern heathens and were caught up in obnoxious ideas of religious superiority. As the illness started to tally up death tolls on trade routes, merchants began looking at the situation closely – but took no precautions. Even the more educated individuals downplayed the Great Pestilence. According to the religious factions, the pious members of the society had no reason to worry.

The people looked up to the Church as it provided nearly all the answers to mortal man. No explanation from the Church – along with its utter failure to keep the death toll down – must have made it seem like the end of the world. People began losing trust in the clergy and started opting for desperate measures. Flagellation became a common way of atoning for sins. People turned to all sorts of mystic ideals as an alternative to the Church. The Church’s inability to provide any sense of security made room for the authority of other religious bodies.

The Church was no longer a symbol of salvation; it was, instead, an authoritarian body with little practical value and a corrupt institution. Less than 150 years later, Martin Luther would nail his Ninety-five Theses to a church door and start the Reformation. While some profited from the Church’s misfortunes, others fared much worse. Without a sufficient understanding of the phenomenon, people started to play the blame game, scapegoating each other to appease their minds. One of the main scapegoats was the Jewish population.

The movement to blame Jews for the Black Death began in Spain and Southern France. Almost a third of the 2.5 million European Jews lived in the region and were often quite wealthy. Everybody joined the cause as an excuse to loot land and fortune. By 1348, the pestilence had reached Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

The disease marched from shore to shore, from town to town, and from city to city, without discrimination. Rich or poor, virtuous or malicious, sophisticated or not, it did not care. Fleas carried the disease and were responsible for its spread, in addition to human spread by airborne contamination.

Maybe Rats Aren’t to Blame for the Black Death

The sickness traveled via any animal with fleas like cats, dogs, mice, and rats, serving as secondary carriers. Researchers believe that rodents were the main secondary carriers, but they disagree on whether it was mice or rats. The proclaimed God-given authorities were not exempt from the punishment – the Black Death killed many members of royal families. The King of Aragon died, as well as the queen consort to Pedro IV. King Phillip VI had left his wife, Jeanne la Boiteuse, to rule the country, who fell victim to the widespread monstrosity.

People were dropping like flies, including higher church officials, so Pope Clement VI kept his place in Avignon smoky to avoid a similar outcome. Princess Joan of England experienced the same fate. She was engaged to be married to Peter of Castile, son of Alfonso XI, one of the most powerful monarchs of Europe at the time.

The marriage celebration turned to tragedy when the entourage arrived in Bordeaux. Slowly, people around her started to fall ill, and finally, she did as well. Francesco Petrarch, the 14th-century Italian poet and one of the foremost figures of the European literary canon, also succumbed to it. The literature of the time reflects the occurrence of this tragedy in many ways. For instance, Boccaccio’s The Decameron starts with a group of people leaving the city for a countryside villa to avoid the Black Death. Similarly, the New Siena artistic movement was snuffed out because painters in the city kept dying. By 1350, the plague had reached Scotland, Scandinavia, and the Baltic region.

At the same time, back in Italy – the country where the plague had initially arrived – began implementing preventative measures. As soon as 1348, Italian cities began instating quarantines for arriving ships. Venice was one of the first cities to implement the measure, and other cities followed suit. All ships entering the city had to stay in isolation for 30 days. Ships were always arriving in Venice, but ships were not an issue in landlocked cities like Pistoia Despite the practical differences, they committed to a similar idea, placing regulations on the import of goods and the arrival of merchants. Roughly 70 percent of the city’s population still died.

Path to Pistoia Urban Hygiene Before the Black Death

Milan learned from Pistoia and enacted several laws to limit the spread of the disease. Italy was the first country that was vigilant enough to implement these measures. On the other hand, Castile, Aragon, France, and England were painfully slow. England was so lazy in its approach that when the plague reappeared in 1665, it suffered heavily. Human loss notwithstanding.

The Black Death contributed to the loss of food and animals. Domesticated animals contracted the plague and died. Similarly, livestock was vulnerable. There was a wool and labor shortage throughout Europe, not to mention the cessation of wars. All of this led to a transformation of women’s role in societies. Due to the population deficiency, women were expected to procreate and were treated somewhat better than previous generations.

They also had to work as there was a labor shortage, but sadly, they garnered no additional rights. After its devastating stint from 1347 to 1351, the Black Death made multiple appearances: from 1361 to 1363, from 1369 to 1371, from 1374 to 1375, in 1390 and 1400. Over the years, the Black Death has persisted and continues to pop up every once in a while in different regions. However, these recurrences are not particularly distressing, as science and reason have caught up to them. Today, the Black Death does not exist as a harbinger of death and destruction but as a reminder of the death and destruction that an unknown disease can visit upon civilization.

Discover more from TS HISTORICAL

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.