Table of Content

- 1 Pandemics in History

- 2 Download this Article in PDF Format

- 3 1. The Plague of Athens This plague swept through the city of Athens

- 4 2. The Plague of Justinian lasted from 541 to 549 CE

- 5 3. The Black Death

- 6 4. The Great Plague of London

- 7 5. Smallpox in the New World

- 8 6. Cholera in London Although the Great Plague of London

- 9 7. The Spanish Flu of 1918 The Spanish Flu pandemic swept across the globe

- 10 8. HIV and AIDS The HIV and AIDS epidemic

Pandemics in History

There have been an estimated six to seven million deaths worldwide during the Covid-19 pandemic. While that’s horrible, it is far from the deadliest Pandemics in history!

This recent pandemic was a sobering reminder that our society can easily crumble under the pressure of microscopic organisms. Viruses and bacteria have held power over the human race for millennia, and history is littered with pandemics that shook the human race to its core. Yet, despite all the death and illness, we continue to come back together and grow. In fact, some people have even used past pandemics to learn more about preventing and lessening the impacts of the next one.

Download this Article in PDF Format

Get a well-documented version of this article for offline reading or archiving.

Download Now (1008 KB)The following eight pandemics are among the worst in history – both in death count and in the cultural scars that have been passed down to us today.

1. The Plague of Athens This plague swept through the city of Athens

Around 430 BCE during the Peloponnesian War. Scholars aren’t sure what the exact disease was. Still, it killed between a quarter and a third of the population in approximately five years, leaving Athens in social chaos and at a disadvantage in the war against the Spartans.

Most of our information on this plague comes from Thucydides, a Greek historian who survived the plague. He described how highly infectious it was, and he mentioned how it began with a high fever and progressed through vomiting, diarrhea, ulcers, and unquenchable thirst.

The doctors at the time were powerless to stop the disease, often catching it themselves while caring for the sick. No remedy seemed to work for everyone, and infected people sometimes found themselves without anyone to nurse them back to health. Although some people did survive, the corpses piled up in the streets; it was not uncommon to burn several bodies together on a funeral pyre.

The city’s overcrowding exacerbated the plague – Pericles had called all Athenians inside the city to protect them from the Spartan army, but Athens was not built to support so many people.

The disease raged in crowded lodgings, and everyone, regardless of social class or wealth, was vulnerable. The instability brought about by the illness led to civil unrest, spiritual questioning, and the end of the Golden Age of Athens.

2. The Plague of Justinian lasted from 541 to 549 CE

Historians believe this was the first time the bubonic plague reached European shores, and it was deadliest around Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

As the rest of Europe crumbled into the Dark Ages after the fall of Rome, the eastern half of the empire lived on as the Byzantine Empire. These people were a light amidst the dark in terms of art, science, and academia in Europe, but even their science could not explain the plague.

Modern scholars believe that the plague reached Constantinople from trade ships returning from Egypt – a recently conquered land. Emperor Justinian was ruling at the time – thus the pandemic’s name – and he brought the Byzantine Empire to its height. Unfortunately, that meant that he also accidentally exposed his people to the plague.

The plague arrived in the ports of Constantinople, but it soon spread; at its height, it was killing about 10,000 people a day. Bodies were piled outside and stacked indoors, and although some people, like Emperor Justinian, survived the plague, there was no medical understanding of what happened.

The plague tore across the Byzantine Empire, reaching Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. There are no firm numbers for how many died, but someplace it at thirty to fifty million people.

The Plague of Justinian marked the start of the decline of the Byzantine Empire; losing so many people to a mysterious illness over a few years was a shock from which they never fully recovered.

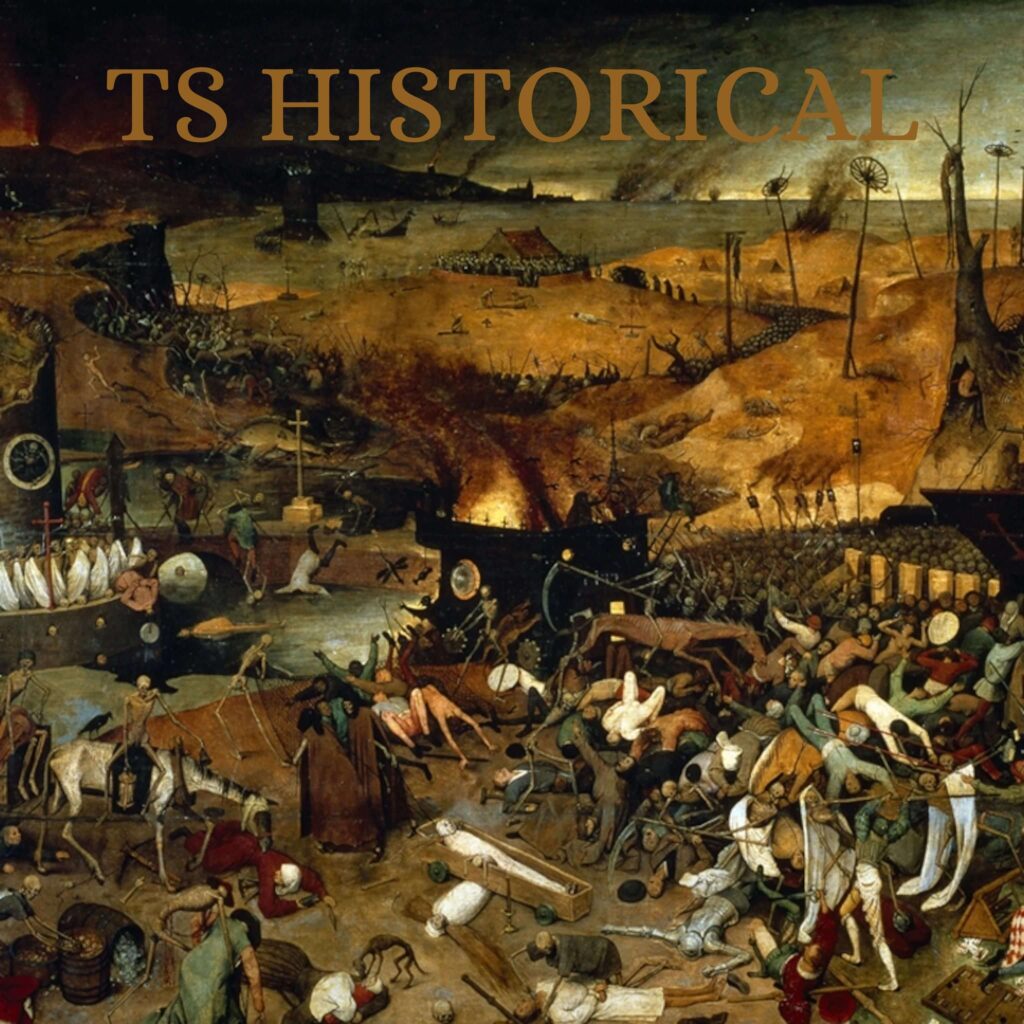

3. The Black Death

main content – Black Death

This is probably the most famous pandemic It was an outbreak of the plague from 1347 to 1351 that killed an estimated third to one-half of the European population..

The epidemic actually started in China around 1334 and slowly moved west, but it did not reach European shores until October 1347, when twelve ships arrived in Messina that would later be called “the death ships.” Most of the sailors were already dead, and the last few were in the final throes of the disease – the people boarding the ship were horrified, and the local authorities drove the boats away. It was not enough to save Europe, though, and the plague spread due to a lack of medical and scientific knowledge.

This was a time of great panic as the Europeans were forced to deal with disease and death on a scale they had never seen before. There was no time for proper burial rituals – bodies were piled in the streets and either cremated or buried in mass graves.

As people died by the thousands, the church began to lose its power over people. Since they had been powerless to stop the plague, people began looking for answers elsewhere.

The Black Death was also an equalizer – no one was safe, which meant the rich were just as susceptible as the poor. As the people began to implement quarantines better, the disease finally subsided. The people came back together and started rebuilding a better life for everyone.

4. The Great Plague of London

The Black Death was not the final outbreak of the plague – it resurfaced in Europe every few years, and London was one of the most notorious places for the outbreaks. In April 1665, London’s last plague outbreak began; it is believed that fleas from infected rodents were once again the cause, but this outbreak would prove to be one of the worst in England.

Before this, England had created laws to isolate the sick – by the early 1500s, it was required that plagued houses are marked clearly – and you were required to publicly disclose if you lived in a house with infected family members. All of this did not stop the Great Plague of London.

Over the course of about seven months, an estimated 100,000 people died in the city and surrounding villages. Infected people were forcibly shut into their houses, and all public entertainment was canceled in an attempt to stem the infection rate.

Historians are not sure what ended the Great Plague; isolating the sick certainly helped, and some historians believe the Great Fire of London also helped. Normally, huge fires are not seen as good things – this one started on September 2, 1666, and burned down a significant part of London in only four days. Although it left massive destruction, the fire also obliterated the plague; there would never be another massive plague outbreak in London again.

5. Smallpox in the New World

Smallpox was endemic to the Old World; the people had dealt with it for centuries and had built up some immunity. Of course, people still died from smallpox, but the death rate in the New World displayed the complete devastation that this disease could bring.

When the first European explorers arrived, they unwittingly brought their diseases; the native people had no immunities and were suddenly hit by catastrophe as smallpox ran through the population, killing tens of millions.

The Europeans brought other diseases, like influenza and measles, but smallpox is remembered as being particularly destructive to the native populations. Historians believe that at least ninety percent of the population died in a little over a century from European diseases; whole civilizations perished from the pandemic, and farmlands were abandoned, which some historians believe led to global climate change as the Earth cooled in the sixteenth century.

Smallpox and other diseases nearly obliterated the population, which actually aided the Europeans’ conquests. As millions of people died, the great indigenous civilizations were too weak to stop colonization. Smallpox and other European diseases famously helped Hernán Cortés defeat the Aztecs in 1521, and Francisco Pizarro conquered the Incas in 1532 by destroying much of the native armies before the battle could commence. As Europeans continued to arrive, they found the European diseases that had gone before had reduced the size of the indigenous groups and paved the way for European conquest.

6. Cholera in London Although the Great Plague of London

The Great Plague of London was the last outbreak of the bubonic plague, London had not finished suffering from pandemics. In the early and mid-eighteenth century, cholera killed thousands of people.

The disease comes from contaminated drinking water – which London certainly had plenty of. London did not have an effective sewer system in the 1800s, so wastewater often came into contact with drinking water. Human waste was often piled in courtyards or overflowed from basements, contaminating the water.

The doctors at the time, though, did not know how cholera spread; they only knew that there was no cure; the rapid onset of symptoms like diarrhea, vomiting, erratic heartbeats, and dry, shriveled skin with a blue tinge frightened the public.

The doctors theorized that cholera spread through foul air called “miasma,” but removing human waste from the streets did not curb cholera outbreaks because the waste was being dumped into the River Thames – the source of most of London’s drinking water.

In 1854, John Snow discovered that cholera was spread through water, not through the air. He determined that the 1854 outbreak came from the Broad Street water pump; although he was able to convince city officials to remove the handle from the pump, the medical community did not believe that cholera was waterborne until 1866.

London began implementing urban sanitation, which ended the cholera outbreaks that had claimed thousands of lives. Some historians believe the cholera epidemic claimed nearly forty thousand lives before it was brought under control with good sanitization.

7. The Spanish Flu of 1918 The Spanish Flu pandemic swept across the globe

The end of World War I, killed an estimated fifty million people before its end in 1920. Interestingly, the Spanish Flu did not begin in Spain. They had never imposed strict censorship on the press during the war because they were neutral, so they were reporting freely on the disease. That meant that people believed the flu started in Spain, which is how it got its name.

The spread of this flu was actually advanced by soldiers returning home from war; the cramped conditions had led to the development of diseases, and the poor nutrition on the home front left many people vulnerable to illness. This pandemic was also a time of panic – the disease devasted both urban and rural areas, and a significant portion of its victims were young adults, who are usually unaffected by seasonal cases of flu.

The virus also moved more quickly than doctors and scientists could; some died within hours of the first symptoms, and others suffocated from fluid in their lungs after just a few days.

The sudden death toll – especially after the deaths and injuries from World War I – had sharp economic effects worldwide. Manufacturing dropped by half in the United States; farming stalled in Africa; famine spiked across the globe.

The pandemic finally ended when enough people developed an immunity to the Spanish Flu, but illness and death were certainly not the welcome home that many soldiers had expected after the war.

8. HIV and AIDS The HIV and AIDS epidemic

Is still ongoing; it probably developed from a chimpanzee virus that crossed over to humans in the 1920s in West Africa. It then spread across the globe, officially becoming a pandemic in the 1980s. (Today, many see HIV and AIDS as an epidemic, as the spread of the disease has slowed and is more localized to certain countries.)

HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus, and it is spread through the exchange of bodily fluids. Once infected, the virus attacks the immune system; eventually, so much of the immune system will be destroyed that the body cannot defend itself from illness. This is called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

When the pandemic exploded, it was met with mass hysteria. There was little understanding of how the virus spread or who it could infect. Since it initially affected the gay community, which was already highly stigmatized at the time, they became even more alienated than they had been before. It wasn’t until 1987 that medication was discovered for treating HIV. There have been other advancements in HIV treatment, but there is still no cure. Still, with early testing and a medication regimen, people who contract HIV can live nearly normal lives.

This pandemic continues to affect life today; Sub-Saharan Africa continues to be severely affected by HIV and AIDS, a situation that is still being studied by scientists to determine if the HIV strain is more virulent in Africa. However, access to medications is ever-improving, giving hope that we may eventually see an end to the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

Discover more from TS HISTORICAL

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.