Narratives and stories play a central role in human understanding of the world. It is difficult for us to conceive of the world without the stories we grew up with. Similarly, all societies and nations have their founding myths, laying the cornerstone of their identity and sense of self.

Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is among the first known historical works of literature and one of the most influential of them all. In retrospect, it is striking how many genres can trace their origins to the text. While primarily an epic adventure story, it contains romance and comedy. It is also the ultimate mythological origin story. It tells the tale of King Uruk, the semi-mythical monarch of Mesopotamia; however, most historians and archaeologists believe that he was an actual figure. Uruk is most commonly identified as the 5th king of Uruk of the 26th century BCE.

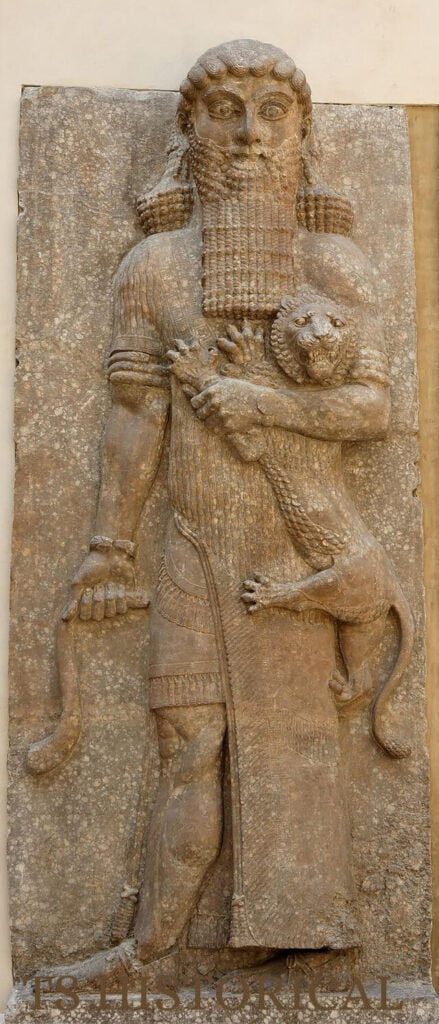

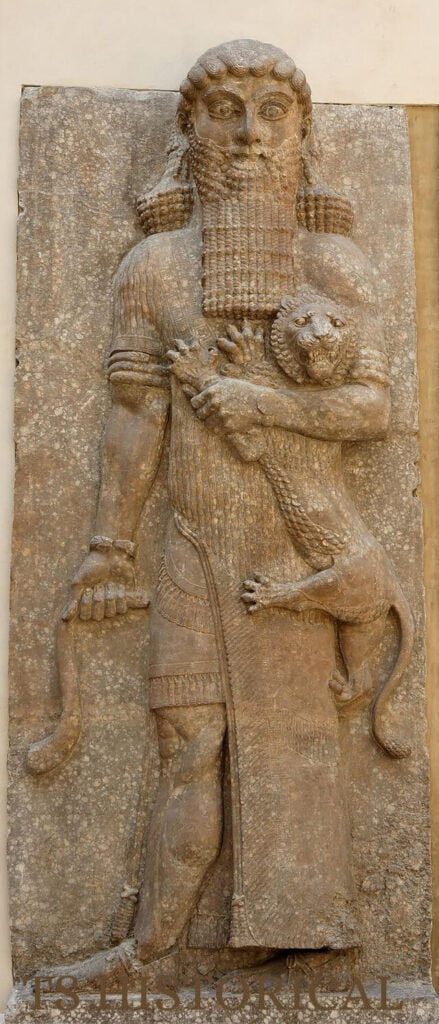

Inscriptions crediting him with the construction of Uruk’s huge walls provided proof of his existence. Indeed, the walls are mentioned in the epic tale, showing at least some connection between the legend and historical fact. As his exploits turned larger than life, he went from being a well-loved monarch to a subject of legends and fables. Many future kings would claim to be descendants to establish their claims to the throne. By the time the Epic of Gilgamesh was written, the historical king had long faded in memory. The story we know is based on several earlier legends of Gilgamesh, which predate it by centuries. For example, we now know that the character appeared in the Sumerian tale of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree. Gilgamesh was the son of Priest-King Lugalbanda, a legendary magician and the subject of epic poetry himself. Meanwhile, his mother was the goddess Ninsun. According to the sources, this Mesopotamian king who lived for 126 years had godly qualities, such as superhuman strength. Later on, Gilgamesh would take on an even more significant religious role as the judge sitting in the underworld. Many clay tablets containing prayers to the figure attest to this fact and the importance of Gilgamesh.

Gilgamesh was a harsh ruler to his people and ruled them as an unforgiving and despotic tyrant in the tale. Therefore, the gods created Enkidu to control him – a wild man who dwells amongst the animals. He challenged Gilgamesh to a trial of strength and was bested by the powerful king. As a result, Enkidu became the fast and loyal companion to the monarch. The two got into all sorts of trouble. They set out to the Cedar Forest beyond the seventh mountain range. The motive? To make an immortal mark on history by claiming the far-flung mountainous area as his own. He reached the forest, which was protected by Humbaba, a monster with the face of a lion. The epic tells us that his “roar is a Flood, his mouth is death, and his breath is fire!” To overcome the protector, Gilgamesh offered Humbaba his sisters and wives as concubines. When the forest’s protector has his guard down, the king overcame him with a punch to the face, and Enkidu proceeded to slaughter Humbaba when he was defenseless. While the Epic of Gilgamesh presents this as a triumph, other traditions do not. A tablet with a different variation of the story claims that under Humbaba, “the paths were in good order and the way was well-trodden.” He was so well-loved by the animals that “like a band of musicians and drummers daily they bash out a rhythm in the presence of Humbaba.” Therefore, what Gilgamesh and Enkidu did was seen as a crime against the rightful protector of the forest. Nevertheless, Enkidu and Gilgamesh were unperturbed by the events of the Cedar Forest and continued their epic adventures. According to the Epic, Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of love and justice, attempted to seduce our hero – but he turned her down.

Enkidu Death

It should be noted that in an earlier Sumerian version of the story, Ishtar did not dry to entice the hero sexually. She did not take rejection well and demanded that her parents, the gods Anu and Antu, give her the Bull of Heaven. Ishtar sent the magical creature to strike down her would-be lover. Unfortunately, the bull did tremendous damage to humanity, almost drying up the Euphrates River, the source of Mesopotamian civilization. It also opened up pits in the ground, swallowing up and killing hundreds. Gilgamesh’s best friend, Enkidu, helped him battle the mighty creature. The sidekick pulled the Bull of Heaven’s tail while the king fatally stabbed him in the neck. It is impossible to overstate the importance of this moment in Mesopotamian culture. Representations of the killing of this divine bull are common and central. Going back to the story, the angry Ishtar responded by standing atop the walls of Uruk and cursing the king. At the sight of this, the loyal Enkidu tears the bull’s right thigh and hurls it directly at the goddess. Not surprisingly, the gods are displeased with Enkidu for this affront and for intervening in their dispensation of justice. Therefore, they sentence him to death. The doomed wild man became deathly ill and dreamed of a “house of dust,” where people ate clay and wore bird feathers. Following these dreams, Enkidu died. The friendship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu provided the lynchpin for this epic tale. The role it plays is similar to the pivotal role the male bond between Achilles and Patroclus plays in Homer’s epic Illiad,

Gilgamesh and the Magic Plant

The origin story of the Greek civilization. The death of his best friend haunted Gilgamesh, and his mourning was intense – the grief of the king unparalleled. He denied that the wild man was dead until a maggot crawled out of the corpse’s nose. Then, the king spared no effort and expense in mourning his friend and paving the way for Enkidu in the afterlife. Using the treasures of his kingdom, Gilgamesh provided gifts to the relevant gods to ensure a welcome reception for his friend in the realm of the dead. It wasn’t merely grief that burdened the mythical king. Instead, confronting his mortality proved too much for Gilgamesh to bear. He cried: “How can I rest? How can I be at peace? Despair is in my heart. What my brother is now, that shall I be when I am dead.” Gilgamesh then left his kingdom to seek out the secret of eternal life, undertaking an epic quest to seek out Utnapishtim, whose name literally meant “the faraway.” Utnapishtim is the lone survivor of the terrible Babylonian Flood, and the king believed that this individual would provide him with guidance to avoid death. On his way, Gilgamesh passed through the twin peaks at the end of the earth, where he had to go through a tunnel guarded by two monstrous scorpions. The arachnids were a married couple, and our hero convinced the wife to allow him to pass. Gilgamesh had to persuade the ferryman then to take him past the Waters of Death and to the abode of Utnapishtim. When he found the man, Gilgamesh asked for the secret of immortality. Utnapishtim reprimanded the king but agreed to tell our hero how he obtained eternal life. Enlil, the god of wind, launched the great flood to destroy all living creatures. However, the god Enki ordered Utnapishtim to build a boat and save himself. So he loaded his family and all the animals of the field onto a vessel built to Enki’s specifications. After surviving the flood, Ishtar condemned Enlili for his disproportionate punishment upon humanity. To appease the goddess, the wind deity granted Utnapishtim eternal life. Therefore, the immortal human had little help to offer Gilgamesh; he had attained immortality as a unique gift in a set of circumstances that could not be duplicated. Gilgamesh was unconvinced. Therefore, the immortal Utnapishtim challenged him to prove. his worthiness. He told Gilgamesh to stay awake for a week; however, the king failed to conquer sleep, proving him unworthy of immortality. Still, Utnapishtim’s wife was sympathetic to the plight of Gilgamesh and convinced her husband to offer the king a parting gift. In parting, Utnapishtim told our hero that there was a magical plant capable of renewing his youth at the bottom of the Waters of Death. The clever Gilgamesh bound stones to his feet, sinking to the bottom of the sea. He obtained the coveted plant and planned to try it on an old man in Uruk. However, while the king bathed, a serpent stole the plant – and with it, Gilgamesh’s last chance at circumventing death. He wept in despair and returned home. The last tablet of the epic is inconsistent with the rest of the narrative. In this section, Enkidu was still alive, and Gilgamesh complained to him that some of his belongings had fallen underwater. Enkidu offered to bring them back, but when he did, the wild man failed to follow his instructions and found himself trapped underwater.

Gilgamesh petitioned several gods to help his friend out of the underworld, and while some ignored his pleas, the solar god Shamash decided to help and bring back the long-lost Enkidu. The epic ends with the eternally dissatisfied Gilgamesh questioning him about the properties of the underworld. However, the bereft king was offered some answers along the way. For example, Gilgamesh met the goddess of beer, Siduri, who told him that his focus on immortality was destroying his happiness. Instead, Sidori suggests that he appreciate the simple things in life, such as the company of friends and good food. It is an example of the advice sages have offered in many cultures: the pursuit of what we can’t have makes us miserable. The story is summarized in its last lines: “O Gilgamesh, you were given the kingship, such was your destiny, everlasting life was not your destiny. Because of this, do not be sad at heart, do not be grieved or oppressed; he has given you the power to bind and to loosen, to be the darkness and the light of humankind.” The epic had been lost to us for many centuries. Finally, however, it was rediscovered in 1849 by archaeologist Austin Henry Layard. Ironically, his mission had been to substantiate the stories of the Bible; instead, he found one of the earlier sources of some of the biblical narratives. If not the direct source, the tale is clearly related to several of the stories in the Hebrew Bible. Most notably, the story of the flood in Genesis and the accounts of the Garden of Eden.

Enkidu was created in a similar process to Adam and Eve. In addition, the role of the serpent is allegorically similar in both accounts. The similarities to other early epics are also evident. The wandering of Gilgamesh, and his wily tricks, are reminiscent of the role of Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey. The discovery of the epic of Gilgamesh has allowed scholars to understand the roots of our most enduring cultural images. Why did this story prove so enduring? The epic tale resonates because it deals with some of the most immutable and central questions of human existence – for instance, dealing with mortality and bringing meaning to our fleeting lives. Though Gilgamesh was unable to find immortality, he found something more important: meaning. Thus, Gilgamesh ironically found immortality by telling the story of his failure to attain it. Although conceived some 4,000 years ago, we continue to see ourselves in Gilgamesh’s desperate search for meaning in the face of futility.

Discover more from TS HISTORICAL

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.